What's in a Name? What if the Name is Chamaepericlymenum?

Untangling the diversity and history of life is a crucial and worthy endeavor, but is constantly renaming and excessively partitioning species a problem? Some of us use these names for things...

The concept of species is one of the first things children learn about the world. This fluffy jumpy thing is a grey squirrel, this cheery, tiny bird is a chickadee. The tree out front is an oak. It’s the most simple thing there is to learn, right? right?????

Turns out the web of life is incredibly complicated. “Oak” for example is a type of tree, but in fact it’s considered a “genus”, which is a level above species. In fact, according to Google, there are over 400 different’ species’ of oaks that have been described. And each species is totally discrete, right?

Wait, what exactly even defines a species?

Well, if you go to Wikipedia, it says this: “A species (pl. species) is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction.”

That’s what i learned when I started out too. The problem is, that doesn’t work well with a lot of taxa (that’s the word for any defined group of similar organisms). Take the oaks… for instance bur oak and swamp white oak. Both grow in the Champlain Valley of Vermont. When you find a classic bur oak, you know it. Its leaves have a unique ‘waistband’, like this:

Then there’s swamp white oak, which is similar, but doesn’t have those deep lobes in the leaves, and the leaves are more pale underneath. Its acorn caps are also less fuzzy.

This all sounds great in this blog post, but then you get out to the Champlain Valley on a hot June day. The mosquitos are awful, there’s a thunderstorm coming, and you’ve got a few oaks in your vegetation plot that you are trying to identify. The problem is, they look somewhere in between the two. And in fact they are somewhere between the two. You’ve found hybrids of bur and swamp white oak. Haines says this hybrid is rare, but i’ve seen it multiple times. Or at least I think I have. Maybe I haven’t, because bur oak also hybridizes with white oak and chestnut oak, and swamp white oak also hybridizes with white oak. And of course, white oak hybridizes with chestnut oak as well. Basically, any of the ‘white oak group’ in Vermont (oaks with rounded leaf lobes) can hybridize, and in some cases, without genetic testing you can’t afford, you won’t know what it is! The red oak group hybridizes too, as red oak can hybridize with black oak, scarlet oak, and others. Many of these (maybe all) produce fertile offspring, which means the hybrids themselves hybridize with other nearby oaks sometimes. And lest you get the impression it’s some Quercus quirk, willows, ash, spruce, and maple do this as well. In fact, in the swamps and floodplains of northwestern Vermont, red and silver oak intergrade into a hybrid swarm of backcrosses spanning the whole range between each species.

So that makes it simple, right? There’s just two species of oak in Vermont, right? Red and silver maple are the same species, right? Except that isn’t very useful. Bur and swamp white can be a headache to tell apart, but white oak is truly different from these, with very different habitat needs. Chestnut oak looks similar to swamp white oak, but it grows on Vermont’s driest hottest ridges whereas true to its name swamp white oak indeed grows in swamps. Outside of the hybrid swarm, red and silver maple truly are very distinct. So, this ‘extreme lumper’ approach doesn’t work well.

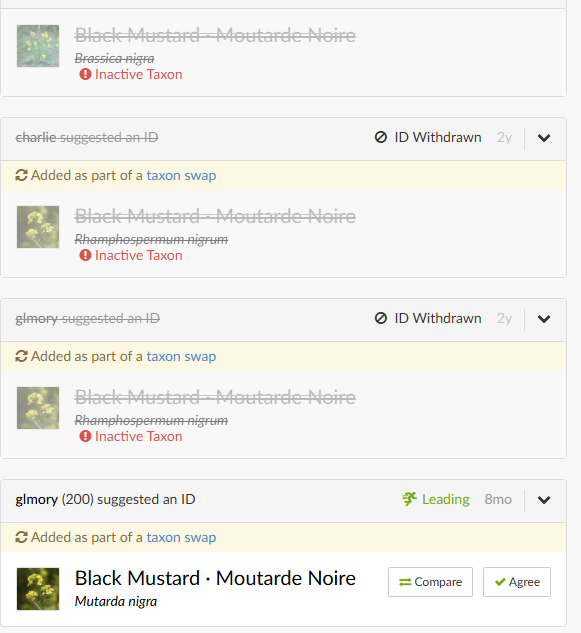

Unfortunately, there’s been a recent push to go far in the other direction instead. Instead of using the hybridization criteria, the new trend is to declare literally any discernable, repeatable difference as its own species. This includes genetic differences. Take ponderosa pine, the enigmatic pine that covers mid-elevation mountains across much of the western United States. Granted it’s very similar to Jeffrey Pine and hybridizes with that species, but it’s got a much larger range and is very distinctive. It’s a good species, right? Not according to some taxonomists. In fact many taxonomic authorities have split it into multiple species. Supposedly they differ in factors like number of needles per bundle, except you have to count hundreds of bundles per tree. This might be a soothing task on a warm summer day as the pines smell wonderful and make the most soothing sound imaginable in a breeze. But… even before the United States said "hold my beer” to the UK and embarked on a binge of national self destruction an order of magnitude beyond Brexit, field ecology was always horribly understaffed and underfunded. Simply put, no one has got time for this pleasant but inane nonsense. It’s not just ponderosa pine either. The new splitter hegemony has stricken again and again, splitting up Joshua trees, foamflowers, Jack-In-The-Pulpit, stinging nettle, already-cryptic Sphagnum moss species, pitch pine, blue cohosh, black mustard, and many more. And dandelions. You don’t even what to know what they did with dandelions. Go look at all of these 'so called ‘microspecies’ here. There’s dozens - hundreds maybe. They may or may not be genetically distinct but you won’t be picking these apart in your releve plot.

Whew! Well, if that isn’t enough, they are splitting genuses up too. And it pretty much always results in your taxa getting a new ridiculously unspellable name that can not be written on a field form. Yucca? Now it’s Hesperoyucca. Many common Scirpus became Schoenoplectus. Some taxonomic authorities have removed bunchberry from Cornus. I don’t find this change too much of a frustration per se because it really is very different from other dogwoods. But the name they use? Chamaepericlymenum. No, that’s not a joke. Someone actually thought that was a good idea, undoubtedly someone who’s never had to follow a protocol that required writing full scientific names on a piece of ‘rite in the rain’ paper that is quickly losing its waterproof qualities while your fingers go numb in a 40 degree downpour. Nor have they ever had to type that into a database 50 times. Sometimes these names are used because some very dead wealthy European man came up with it over a century ago and other times the names were created very recently. Some of them are quite poetic really, but you won’t see me writing Mary Oliver’s Wild Geese 20 times in a sodden notebook in a spring downpour either. The soft body of my animal says f***k no to that one too.

What is there to be done? For most people, the answer is to ignore the new names. This of course causes lots of problems as some names are adopted and others are not. Any use of this approach makes field work nearly impossible and mangles database back-compatibility. It’s even worse on iNaturalist. iNaturalist has firmly adopted the approach of adding any possible proposed taxon split any graduate student has ever written in an unpublished, unreviewed paper based on supposed stolons you can see only on Tuesdays during a lunar eclipse. If you try to add a ponderosa pine, as your kindergarten teacher and all field guides describe it, you’ll get scolded. I was a curator for a time and advocated for less ridiculous taxonomic change, but just gave up under a stream of attacks on my integrity, credentials, and even an anonymous hate mail. Seriously, i’m a veteran of AOL chat rooms back when the internet was truly anonymous, and some of these ‘curators’ would give CreepyDude69’s random “ASL” IM chains a run for their money. Oh, and they all have moderation privileges as well, which CreepyDude69 didn’t. And you probably don’t either. Some of them are quite happy to abuse their power. Unfortunately, humans gotta human and iNaturalist’s onetime title of ‘nicest place on the internet’ was sadly fleeting. Taxonomic inflation (among other things) has taken its toll.

There’s another factor at work here too. There’s the idea that if you declare these minute variations as their own species, more things are tracked as rare, and more species will get protected. There are two problems with this. One is that it’ll be nearly impossible to monitor things that are nearly impossible to tell apart. The other is that those of us in the USA are dealing with people who would literally declare a leaking oil drum the head of the EPA if they could get the Supreme Court to grant it personhood. They are not going to suddenly conserve cryptic species just because someone’s genetic analysis proves it is technically distinct. No, just stop with this. Locally appropriate ecotypes and disjunct or edge-of-range populations need protection, but declaring everything its own species isn’t going to go the way you think it will. It leads to impressive species lists, and a lot of ‘rare’ species and probably used to be a decent way to get grant funding. But it isn’t doing ecology any favors.

Ok… wait a minute. Don’t send me that hate email yet. Hear me out. I absolutely believe that the field of genetics is a gamechanger for ecology, that it’s worth tracking the evolution and genetic ancestry of populations, and it’s a worthwhile endeavor and an act of love to describe every little variation of a species as it’s own entity. Look, i’m autistic af, i completely get the urge and support it. Just… maybe consider making Eclipse-Stoloned False-Foamflower a subspecies or variety instead of a species next time? No one gets grant money any more anyway. Let’s actually create a naming system that will still work in this proto-apocalyptic wasteland, okay? And don’t let CreepyDude69 describe any new species of dog stinkhorn mushroom, that just isn’t going to go well.

The world is incredibly complex, and that’s awesome! Just.. some things don’t need to be complex for no good reason. Consider limiting the length of your new genus name, please. The Rite-In-The-Rain paper doesn’t work that well anymore, and seriously, some protocols really do make you write the whole name on a field sheet. And seriously… what is the deal with Chamaepericlymenum? I don’t care if Linnaeus and Charles Darwin penned the name together on the Beagle. They are dead now and won’t care… just stop.